She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World (27 August 2013 – 12 January 2014) a photography exhibit curated by Kristen Gresh at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), had a surprise at its heart—that images of seemingly passive subjects, such as a veiled woman or a listless harem girl, could in fact be powerful agents. Emphasizing the voices of the powerless, the show evoked James C. Scott’s exposés of everyday forms of resistance (as described in his book Weapons of the Weak). The work by these Arab and Iranian women photographers conjures up the realization that the binary notions of controlled and controlling, powerful and powerless, and compliance and defiance, are not neat and clear-cut.

During its five-month run, She Who Tells a Story received widespread media attention and many reviews. While some admired the show, others cautioned against falling once more into age-old Orientalist tropes. They warned against projecting the same Middle Eastern stereotypes—by depicting the veil, censorship, war, and violence—rather than capturing its realities. Writing for Jadaliyya in October, Katie Cella saw it as “yet another rescue attempt, a curatorial framework that ‘allows’ women of the Middle East to ‘tell their own stories,’ or prove their social merit by depicting politically frenetic or war-torn scenes. Such a lens does nothing to ‘normalize’ artwork from the Middle East.” The title of the show itself called to mind Orientalist tendencies, evoking the legendary storyteller Scheherazade from One Thousand and One Nights. Some of the curatorial decisions made such implications even more pertinent, as Cella aptly argued. However, like Scheherazade, the artists featured in She Who Tells a Story were engaging in a different kind of negotiation for claims to power. Indeed, there seemed to be a discrepancy between first impressions (or curatorial framing) and the real intentions of the artists. Cella pinpointed this contradiction by commenting that most of the artists “attempt to erode the false dichotomy and take up more nuanced forms of representation.” To concur with Cella, the photographers seem to have mastered a thought-provoking visual language, one that owes its distinctiveness to its indirectness. Although it might appear at first that they are repeating stereotypical imagery (e.g., veiled women and war-torn settings), on second look it becomes apparent that each artist is employing individual techniques that undermine the viewer’s expectations and connect their work to global art practices.

Tehran-based Gohar Dashti’s protagonists are photographed against the landscapes of war, a parched land in the south of Iran that served as a battleground for the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988). This barren landscape is now home to dilapidated war machinery left over from the conflict. Today’s Life and War (2008), a series of images depicting a newly married couple running mundane errands and hanging laundry on barbed wire (Untitled # 2), suggests how ordinary Iranians are neither insensitive to nor paralyzed by the lingering effects of that war. This curious juxtaposition of quotidian activities and armed conflict also animates the NIL series (2008) of another Tehran-based photographer, Shadi Ghadirian, which depicts the remains of the war (a rifle grenade) against the remains of the day (an unmade bed). Such ironic imagery gives the impression that life goes on, as mundane as can be, during war and in its aftermath.

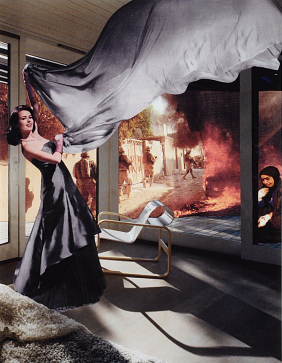

These bold juxtapositions of domestic images with war paraphernalia differ from the work of American artists who have tackled similar issues. Take, for example, Martha Rosler and Barbara Kruger, who are well known for their political art. Unlike Rosler’s The Gray Drape from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home and Kruger’s Your Manias Become Science, the Middle Eastern photographers at the MFA calm the aggression of violence and war by avoiding turning distress into angst and by shying away from translating horror into hatred. Living and working in Iran, in the face of power, they employ indirection. Experiencing war at home is certainly more traumatic than witnessing it via mass media. It is curious that the artistic expressions of the former are all the more subdued. While dealing with similar subject matter, artists’ geographical proximity or remoteness and their degree of engagement with war ultimately allow for different responses.

[Left: Martha Rosler. The Gray Drape, 2008. Inkjet print on paper, 37 1/2 x 29 in. Courtesy of Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Purchase Fund, 2009. Photograph by Lee Stalsworth. Right: Gohar Dashti. Untitled #2, 2008. Inkjet print. 70 X 105 cm. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. ]

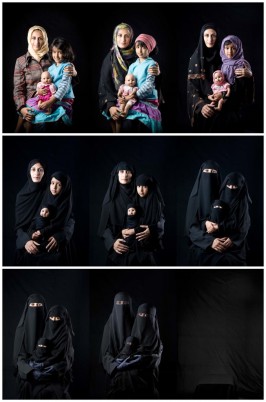

The photographs of Yemeni artist Boushra Almutawakel, who addresses issues of veiling in Mother, Daughter, Doll, 2010, manifest a playful commentary on the role of women in Islamic societies. In nine consecutive frames, we witness a woman with a young girl sitting on her lap gradually disappearing into the darkness of the utmost conservative form of veiling. In each successive frame, the woman, the child, and the doll are increasingly covered by black veils until the photos reach absolute darkness. This whole cinematic tableau is part of Almutawakel’s Hijab Series (2008-2012), which is broader in scope than portrayed at the MFA. In the full series, at times men are also covered and women are unveiled. The curator’s selection of Mother, Daughter, Doll may attest to the general public’s fascination with veiling in Islamic countries. However, even these nine selected frames affirm a form of resistance: that the woman’s identity remains amid the efforts of social structures to regulate it.

Almutawakel’s censored subjects evoke other examples of removal of women’s images. Take, for example, the purposeful obliteration of the heads of Storyville prostitutes in New Orleans by photographer Ernest James Bellocq in his work, such as Untitled, 1912. Consider also the way Iranian government censors obscured faces and bodies of Western women whose images are imported via mainstream magazines. Almutawakel’s erasure is of a different kind. It addresses the thorny subject of women’s oppression in patriarchal society. But her cinematic style constantly loosens this reality of exclusion and subjugation. Instead, the series conjures up hope for women’s perseverance and continuous presence in the face of power.

[Boushra Almutawakel, Mother, Daughter, Doll, 2010. Pigment prints. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, purchase with funds by Richard and Lucille Spagnuolo.]

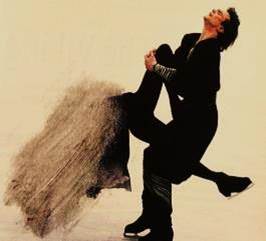

[Left: An image censored by Iranian authorities in 1992. Private collection of the author. Right: The original image from the 1992 Winter Olympics, Unified Team Marina Klimova and Sergey Ponomarenko in action during Mixed Ice Dancing free program at Olympic Ice Hall. In M. Duffy, “When Dreams Come True,” Time 139 (2 March, 1992): 49. Photograph courtesy of the photographer Neil Leifer, Sports Illustrated, Getty Images.]

Consistent with the theme of undermining viewer’s expectations of reality were examples of appropriationist art from Iran and the Arab world. In her untitled photographs from Qajar Series, 1998, Ghadirian appropriates historical images of women in studio settings. She stages women dressed in Qajar style holding items of twentieth-century consumer culture, such as stereos, Pepsi cans, and banned reading material in photography studios modeled after those of the nineteenth-century. These anachronistic juxtapositions may have been intended to invoke nostalgia or the tensions between traditionalism and modernity and even censorship and freedom (as the label adjacent to the series conveyed). But they also allow for further readings: A woman may be confined, a woman may be just a puppet on stage, but she still exercises her freedom in the particular domain of consumerism. In one photograph (Untitled), the protagonist is holding a can of Pepsi. It calls to mind Andy Warhol’s Coca-Cola manifesto: that all humans are equal in the face of global consumer culture and that everyone should be free to practice their choice in this consumerist world. Conversely, also reminiscent of Warhol, Ghadirian courts an active role for the viewer: live as you like and consume (images or otherwise) as it suits your hidden desires.

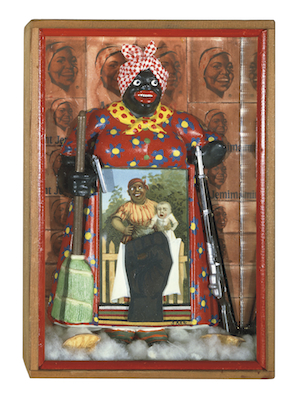

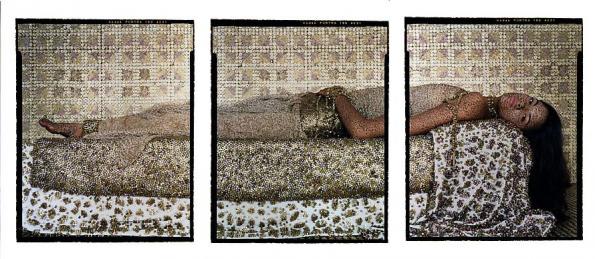

Lalla Essaydi’s triptych, Bullets Revisited # 3, 2012, showcases a woman reclining in a clichéd harem-like position with her body covered by silver and golden shell casings, which, at first glance or even second, look like decorative beads. This photograph could be regarded as an example of post-colonial appropriation. The violation of the softly erotic European male-dominated realm of Orientalist photography places the viewer in a curious position. What are we to make of a listless girl covered with bullet shells? The work brings to mind Malek Allula’s book Colonial Harem (1981), which includes a large collection of French postcards made up of erotic photographs of Algerian women. Allula’s book was envisioned as a long overdue “postcard” that had to be returned to its original destination. Like Allula, Essaydi reclaims and empowers the colonized subject by “arming” her. In this sense, Bullets Revisited # 3 is not too far afield from Betye Saar’s 1972 masterpiece, Liberation of Aunt Jemima, a mixed-media piece animated by a sculpture of the American commercial icon Aunt Jemima holding a rifle, set against a series of collaged Aunt Jemima advertisements. In Saar’s piece, a traditionally inferior black woman is turned into a potent rebel, claiming her agency in American society. In Essaydi’s, a harem girl is oddly made all the more sumptuous and defenseless via bullet casings. Is she a mute and passive subject of our gaze? Or does she leave us powerless in the presence of her unblinking stare and her “armed” body? Indeed, who is powerful and who is powerless here? Where is the line between being the one controlling and the one controlled?

Ghadirian and Essaydi acknowledge the subjectivity of art and by doing so they rub shoulders with activist artists in the US. Whether by condemning racism (Liberation of Aunt Jemima) and criticizing the Puritan codes of Americana in the American Gothic icon (Gordon Park’s 1942 photograph, Ella Watson) or reproaching the mayhem committed by US soldiers in Iraq (Copper Green’s 2004 posters, iRaq: 10,000 Volts in Your Pocket, Guilty or Innocent), American appropriationists have created art by turning recognizable aspects of popular culture into a site for contested meanings. Although far less obvious than in the United States, where appropriationists and culture jammers rewrite the messages of canonical and eminent imagery from art, media, and advertisements, Essaydi and Ghadirian produce criticisms of a socio-political order, but they do it indirectly, by undermining expectations. To follow Scott, they seem to have generated their own “distinctive forms of quiet resistance and ‘counterappropriation’…[indicating] that resistance is not necessarily directed at the immediate source of appropriation.” (Weapons of the Weak, 34-35)

[Left: Betye Saar. The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972. Mixed media assemblage, 11 3/4" x 8" x 2 3/4". The University of California, Berkeley Art Museum, purchased with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY. Photograph by Joshua Nefsky. Right: Lalla Essaydi. Bullet Revisited #3, 2012. Chromogenic Print, each panel is 50 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist and of Edwynn Houk Gallery, NY.]

Women in public urban spaces are the subjects of Rana El Nemr’s work. Here she takes us to Cairo’s Metro. Creating an objective recording while maintaining a surrealist play distances El Nemr’s work from documentary photography. Indeed, by capturing the backs of women standing against the train doors (Metro # 7, 2003), El Nemr removes the direct interaction between viewers and her protagonists and eradicates the complicity between her lens and her subjects. Her subway shots evoke Walker Evans’s Subway Portrait (1938–1941), captured through his hidden camera, which aimed at documenting everyday life in its most truthful sense. However, unlike Evans, El Nemr defamiliarizes the mundane, inviting the viewer to engage in other ways of relating to Egyptian women besides scrutinizing their faces, such as the extent to which they find room for themselves in a male-dominated public space.

[Left: Rana El Nemr. Metro # 7, 2003. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Right: Walker Evans. Subway Passengers, New York City (Two Women in Hats), 1941, Film negative, 35mm. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walker Evans Archive, 1994 (1994.253.575.1), and Art Resource.]

The Iraqi-Irish Jananne Al-Ani’s aerial footage of desert topography, Shadow Sites II, 2011, part of a sequence that examines the real and imagined landscapes of the Middle East marked the end of the MFA show. Al-Ani’s video installations feature aerial footage of manmade edifices dwarfed by immense landscapes. Coupled with the audible drone of an airplane engine, the aerial perspective suggests the US military surveillance of the region. Among the works featured in She Who Tells a Story, Al-Ani’s was unique in addressing the attempted “remote controlling” of the Middle East by the US government. This heavy political message seemed, however, to be somewhat sidetracked by formal features. The work took on an abstract quality, especially when watched over and over. Such repetition slowly drew attention to the harmonious balance of sound and texture and to the cyclically shifting viewpoints. Indeed, one could easily be mesmerized by the moving picture and the almost meditative soundtrack rather than respond to the critical undertone. We can place Shadow Sites II in the same category as the surveillance-inspired works of the French photographer Sophie Calle (The Shadow, Detective, 1985) or those of the Danish artist Niels Bonde (The Art of Detection: Surveillance in Society, 1997). Al-Ani’s work, however, is more abstract and removed from its original source of inspiration.

[Left: Niels Bonde. The Art of Detection: Surveillance in Society, 1997. Cave-table, chair, blankets, monitors, radio scanners. Courtesy of the artist. Right: Jananne Al-Ani. Detail, Aerial I. Production still from the film Shadow Sites II, 2011. Single channel digital video. Courtesy of the artist, Abraaj Capital Art Prize, and Rose Issa Projects. Photograph by Adrian Warren.]

If there is indeed a distinctive characteristic to contemporary Middle Eastern art, then there may be ways to further foreground it in curatorial practices and scholarly works. What I hope to have shown here is that contemporary art of the Middle East needs to be further interrogated by, for example, being compared against analogous examples from other parts of the world. Thus, to enhance Cella’s call for “normalizing” artworks from the Middle East, we may explore what other artists have done when confronting those tropes of veil, censorship, surveillance, violence, and war. Accordingly, comparative considerations may help direct us to what Homi Bhabha calls the translational dimension of art rather than its transcendent capacity. Indeed, in this global village of virtual social networks—where we have an abundance of access to information and ideas—artists’ perceptions of socio-political events may be fundamentally similar and even mutually influenced by those of other artists and yet delivered in contrasting ways. The meaning of art must thus be searched in interstices—those in-between spaces where ideas and sentiments are translated.

![[Gohar Dashti. Untitled #2, 2008. Inkjet print, 70 X 105 cm. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/GoharDashti_postphoto.jpg)